In working with students on research projects and inquiry based learning activities, the biggest challenges I see students facing are the ability to decipher what information is important and the ability to accurately read the information. I find that the ‘reading level’ of most of what students dig up in a Google search is far above their reading level. As a result, students tend to pick out one sentence or two without really digesting the information correctly. This leads to some hilarious mixed up ‘facts’ and research projects or essays that are cut and pasted together.

As such, I applaud the emphasis on “instruction or guidance reference services that teach or direct students to locate information themselves” (Riedling, 2013, p. 5). I liken this to the old adage,

“Give a man a fish, you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.”

(Image retrieved from: https://pixabay.com/p-1545695/?no_redirect)

I want to give my students the skills to support life long learning! There is no point asking students to memorize and regurgitate facts. To be successful throughout their school ‘career’ and beyond, students must “know how to learn because they know how knowledge is organized, how to find information, and how to use information in such a way that others can learn from them” (Riedling, 2013, p.7).

I appreciated the descriptions of the roles Riedling gives to a librarian in chapter 1. A librarian is a:

- “Provider of quality information resources” (p. 4)

- “guide for using information resources effectively” (p. 4)

- “mediator between the perplexed student and too much, or too little, information” (p.4)

- leader who “leads students to information, not knowledge” (p.5)

In regards to changes in our society, Riedling (2013) states “our complex, global society continues to expand at a rate beyond the capacity of individuals to comprehend” (p.10). I disagree; I don’t think our society is expanding at a rate that is beyond our ability to understand. Rather, I think that the way we understand, view, access, evaluate, organize and use information needs to change. If I was to take Riedling’s viewpoint at face value, I would simply give up trying to understand the world around me as it is “beyond my capacity”. I would rather challenge her view and celebrate the abundance of new information by finding new ways of acquiring, accessing, evaluating and organizing the abundance of information available to me.

This is what excites me as a teacher-librarian. How can I model, teach, guide, and inspire students to access, evaluate, organize and use the information that is so readily available to them? I don’t want to sit around bemoaning the fact that there is too much information; let’s embrace it and inspire a generation of lifelong learners.

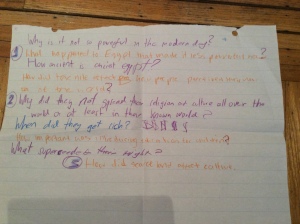

In reading the various research models, my mind was already swirling with an idea of how to further incorporate my evening UBC learning into my day-to-day classroom teaching. What topic are we covering in grade seven that I can use as a ‘test-case’ for implementing one of the research models? (Information Seeking, Big6, Research Process, Points of Inquiry, Research Quest) Well…I am just getting ready to launch a social studies unit on Ancient Egypt. Hmmm, perhaps this is the perfect opportunity to really guide and inspire the research process.

Based on the readings in theme one, here is my outline of an initial draft of my plan to use a combination of the Research Quest Model and the Big6 Model:

- Define the Task

- Question Formulation Technique (http://rightquestion.org/education/) (This organization is free to join and gives you access to excellent resources for implementing the Question Formulation Technique: well worth the time to sign up!)

- Stimulate access to prior knowledge with a Question Focus and provide an opportunity to brainstorm many questions related to the topic

An idea for Question Focus: Ancient Egypt was one of the greatest and most powerful civilizations in the history of the world. Ancient Egypt was rich in culture including government, religion, arts, and writing.

Following our session on brainstorming, students browse through the following websites to narrow down their own research question.

10 Surprising Facts About Ancient Egypt

Another great resource to teach how to formulate excellent questions is Jan Richardson’s (2009) book “The Next Step in Guided Reading” by Scholastic. Pages 210 and following give explicit instructions on teaching the skills of turning facts into questions. She talks about three levels of questions:

- Green questions (literal questions in which a student can go directly to the text to find the answer)

- Yellow questions (complex questions which require students to search in several places in the text: slow down and look… These include cause/effect; compare/contrast; main idea/details)

- Red questions (inferential questions in which the student must stop and think about the text as the answer is not found directly in the text. These include I wonder…; Why do you think…; What would happen if…)

Although I used this with my grade three students, it would be a great exercise for reading nonfiction and fiction at all levels.

My Research Plan (as it is unfolding in my grade 7 Social Studies Classes)

- Students record and submit their research question on their Research Plan

- Outline the research process and teach Information Seeking Strategies

To introduce the Big6 Model, have students watch the following:

Library Queen E. (Aug. 23, 2015). [Video file]. The Big 6 Model for Research. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaKbYcoeGi0

Register, A. (Sept. 23, 2012). [Video file]. Big 6-Anna Register-Big 6. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qEmCfinUQAg

Vierira, D. (Jan. 29, 2015). [Video file]. Big 6 Research Model. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Acynozl1LbQ

For more resources, check out Big6 Helpful Resources

(I must say that my classes thought these videos were rather cheesy, but funny. Considering the way they were laughing and singing along, I would venture to guess that they will remember some, if not all, of the concepts of the big6 model.)

- Location and Access

- School library

- Selecting resources

- Print resources first (appropriate reading level; get a general sense of what the topic is; collect many facts…)

- Non-print resources (websites; ERAC databases; online encyclopedias, video…)

(I explained the art of browsing for resources through the analogy of shopping for clothes) A great article to refer to about the merits of browsing for sources can be found at:

Mongtomery, B. (2014). A Case for Browsing: An Empowering Research Strategy for Elementary Learners. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), E5-E9. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/NovDec14_OE2_Montgomery.pdf

- Use of Information: Gathering relevant information

- Use index cards to gather facts (one fact per card; with author’s name on the back)

- Teach how to access digital sources through school library database

- Sort cards into subcategories

- Organize within categories into paragraphs

- Cite sources

- Synthesis: Present paper or information in some format

- Students choose a format for presentation

- Decide on a presentation style (brainstorm options), class-generated rubric

- Model how to correctly cite works within the presentation and how to include a Works Cited page

- Suggestions for a format to share your information may include (but are not limited to)

- Read aloud to small group?

- Create a few slides in a power point? (limit number of words per slide and the number of slides…)

- Ignite presentation style (20 slides, with 15 sec. per slide)?

- Create a true/false listening guide for students as they listen to your topic. Organize information; review, revise, edit

- Evaluate the process and the product

- Answer the reflection questions on student Research Plan

- What did I learn about the topic?

- What worked well?

- What will I do differently next time?

- What did I learn about research?

- Answer the reflection questions on student Research Plan

As part of the research process, students will also be introduced to different rubrics to evaluate print and non-print sources using the C.R.A.A.P. acronym.

![CCBC Library. (Dec., 2016). Evaluate It!: C.R.A.A.P. Criteria. Retrieved from http://libraryguides.ccbcmd.edu/evaluate-it/craap [Date accessed January 15, 2017].](https://ydewith.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/screen-shot-2017-01-15-at-7-14-41-pm.png?w=300&h=271)

Critical Evaluation Guide for Web Sites

For a funny video about applying the CRAAP evaluation criteria, check this one out!

Bauman, C. (Dec. 30, 2013). [Video file]. The CRAPpy Song (aka, the C.R.A.P. Test Song). Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMaLec2XWY

I like the phrase “information skills continuum” (LIBE 467 Course Content, Theme 1, Lesson 4) in regards to developing literacy skills and the skills needed to move from print to online sources. I wholeheartedly agree that students waste an abundance of time online searching and searching for that perfect website or article that will magically answer all of their questions. Print sources, on the other hand, are a great starting point at the focus stage. When doing research projects with my students, I am a bit of a traditionalist and I insist that they must first collect a certain number of facts from print sources before moving to digital sources. I explain the ‘saturation’ point of fact-finding (that point when the books you have available are repeating the same information).

Alas, not all of my students agreed with my stance on promoting the value of print sources and questioned my wisdom in insisting that books must be consulted! But, my quest to teach research skills that last a lifetime continues on.

We have now moved on to learning how to effectively use electronic sites to continue our search. This led to more mini-lessons on how to choose search key words, how to access and use a few databases available on the school site (through EBSCO) and how to evaluate websites critically (compare sites such as Wikipedia with other sources).

This week’s lessons include how to choose an appropriate presentation format to suite your information and personal style and how to develop a class-generated rubric for authentic assessment. I must say that this Ancient Egypt project is taking us down many more rabbit trails of information literacy skills than I had originally thought! However, as the students are learning about a specific topic related to our overarching theme, they are learning so much more about the skills of “research”. I am curious to see what the students will say in their reflections.

References

Asselin, M., Branch, J., & Oberg, D. (Eds.). (2003). Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Association for School Libraries.

Bauman, C. (Dec. 30, 2013). [Video file]. The CRAPpy Song (aka, the C.R.A.P. Test Song). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMaLgec2XWY [Date accessed: January 16, 2017).

Beeghly Library. (n.d.). The CRAAP Test Worksheet. Juniata College. Retrieved from http://legacy.juniata.edu/services/library/instruction/handouts/craap_worksheet.pdf [Date accessed January 15, 2017].

Byerly, G. & Brodie, C.S. (2007). Fifty Nifty Websites: Choosing Them was Fun! School Library Monthly, 23(9), 39-41.

CCBC Library. (Dec., 2016). Evaluate It!: C.R.A.A.P. Criteria. Retrieved from http://libraryguides.ccbcmd.edu/evaluate-it/craap [Date accessed January 15, 2017].

Glenbard High School Library [website]. (n.d). Evaluating Sources. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/a/glenbard.org/diglit/home/evaluating-sources [Date accessed January 15, 2017].

Mongtomery, B. (2014). A Case for Browsing: An Empowering Research Strategy for Elementary Learners. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), E5-E9. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/NovDec14_OE2_Montgomery.pdf

Richardson, J. (2009). The Next Step in Guided Reading. Scholastic Canada Inc.

Ron E. Lewis Library. (2016). Thinking Critically about Web Information- Applying the CRAAP Test. Retrieved from http://library.lsco.edu/help/web-page-rubric.pdf [Date accessed January 16, 2017].

Rowly, J. & Johnson, F. (2013). Understanding trust formation in digital information sources: The case of Wikipedia. Journal of Information Science, 39(4), 494-508.

Southern New Hampshire University Library: Shapiro Library. (2016). CRAAPO- Source Evaluation Rubric. Retrieved from http://libguides.snhu.edu/ld.php?content_id=13078862 [Date accessed January 16, 2017].

Wexelbaum, R. (2012). Is the encyclopedia dead? Evaluating the usefulness of a traditional reference resource. Reference Reviews, 26(7), 7-11.